This post demonstrates the power of operations science in healthcare services, no massive investment in technology or dogmatic continuous improvement efforts required. It is a synopsis of the case study Nurse Scheduling At St. Mary’s Hospital excerpted from Hopp, Wallace J.; Lovejoy, William S.. Hospital Operations (FT Press Operations Management) (pp. 321-337). Pearson Education. Kindle Edition. The full case study is available for download here.

St. Mary’s Hospital is a large, tertiary care hospital on the east coast. Like many hospitals, St. Mary’s was seeing its margins squeezed as a result of decreasing reimbursement schedules; increasing material, technology, and information costs; and an increase in the number of uninsured or underinsured patients it serves. The hospital prided itself on high-quality, patient- and family-friendly care, which it accomplished through its dedicated workforce. The majority of St. Mary’s labor costs were for nurse and staff salaries, which accounted for a high percentage of its operating costs. CEO Bob Driscoll wanted to look carefully at his labor costs to see if there were any potential savings that could be achieved without compromising patient care.

The progression of events in ultimately realizing a significant cost reduction while improving nurse (and doctor) satisfaction while providing excellent patient care were as follows—

- Bob hired consultants who recommended more efficient use of capacity by “shaping demand” for nursing units. The idea was that more evenly balanced patient loads on nursing units would reduce variability and thereby match patient demand more closely with nursing capacity. The reduction of variability to increase capacity utilization is a sound operations science concept. Unfortunately, the solution resulted in no cost reduction, was not completely implemented, and caused significant dissatisfaction among nurses and doctors.

- Bob then went back to the drawing board using his understanding of operation science and, working with his team and no consultants, devised a successful solution of effective flex capacity.

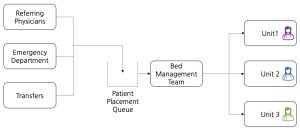

The first step in applying operations science concepts to a process is describing the process, its associated resources and flows. A simple process illustration for St. Mary’s patient placement process is provided below.

Demand for the nursing units came from sources such as referring physicians, the Emergency Department, transfers within the hospital, e.g., “step down from an intensive care unit bed, or between hospitals. St. Mary’s had a bed management team (BMT) of four people who took requests for beds and matched these demands against the bed availability in each unit. Bed availability was tracked on a bed board, which was a visual display of all the beds in each unit and the status of each (occupied, awaiting discharge, empty awaiting cleanout, or available). The BMT then matched patients to available beds, taking into consideration the referring physician’s recommendation.

In some cases, a particular patient designation was “mandatory” due to the nature of the patient’s disease. For example, patients with arrhythmias should go to a Cardiology unit, and patients for chemotherapy should go to a unit equipped with infusion chairs and with a trained staff for that activity. In other cases, one or more units may be preferred but not mandatory. For example, there are preferred places for patients with bronchitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary medical problems. In still other cases, no particular unit was preferred over all others.

Nurses on different units were trained for, and more experienced in, different types of diseases. The common intuition was that patients are best served by nurses most experienced with their particular ailment and, in some cases data (lengths of stay, complications, or adherence to checklists of standard best practices) confirms this. However, patients did not always end up on St. Mary’s recommended unit. When a patient was put in a non-ideal unit, it was known as boarding the patient on that unit. There were several reasons for boarding patients. First, each nursing unit had finite capacity, and if a unit was already full, it was not possible to place another patient there until someone was discharged, regardless of that patient’s recommended designation.

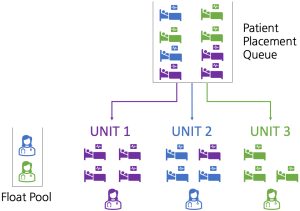

The illustration below shows the initial practice followed by the BMT. The colors represent specific groups of nursing experience, for instance, cardiology, oncology, and labor and delivery. In general. Note that Unit 2 has a “boarded” patient.

Frequently, due to the mismatch between demand and capacity, nurses would be scheduled but then not needed. They could then either go into a float pool and be assigned to any unit or go home and be on call for their particular unit at reduced pay for their on call time. The consultants that Bob hired knew that reduced variability in demand on the nursing units would enable more efficient use of nursing capacity which would reduce cost. However, their recommended solution focused only on reducing demand variability.

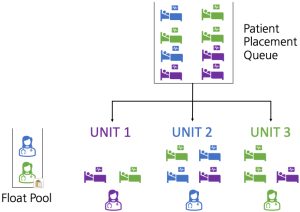

The patient placement system that the consulting firm recommended would begin a day by assigning patients to their “proper” unit (as determined by the referring physician), but after a certain target census in the unit, newly admitted patients (without a mandatory destination) would be assigned to the other nursing units in a fixed sequence, regardless of the patient’s original designation. For example, the next five arriving patients might go to units 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 in that order regardless of where they were “supposed” to go. The logic behind this was that the responsible physicians would still be from the “proper” unit even if the patients were housed in a different place in the hospital, and by honoring the mandatory assignments, this system would not compromise clinical outcomes. The belief was that nurses were skilled enough to follow the instructions of doctors from any discipline, and the rotated patients were not those for whom a “must” designation applied. This approach is shown in the following illustration

Note that patient morbidities, as represented by color, are not well matched to nurse experience. The belief was that nurses were skilled enough to follow the instructions of doctors from any discipline. The consulting firm did a simulation of their recommended solution and forecast that its solution would result in significantly lower nursing labor costs. This is fairly typical of consulting analysis, a detailed simulation shows lots of effort and usually provides good “eye-candy” for the client. If the client is not familiar with operations science, they will have to take the consultant’s recommendations at face value.

In this case, it seems that Bob was indeed familiar with operations science but did not anticipate the consequences of the new patient placement system. After six months with the new system, St. Mary’s had not yet realized the forecasted cost savings. Bob was also receiving an increasing number of complaints about it from physicians and nurses. Physicians did not like the increase in the number of boarded patients that resulted from the new system. Not only did doctors have to walk further on rounds, they had to deal with multiple nursing units, each with different staff and practices.

The physicians complained to Bob that this was inefficient and possibly even dangerous because medical outcomes might be compromised due to patients being placed with staff unfamiliar with their particular disease. Surprisingly, the nurses also complained. Bob had anticipated that more reliable staffing, with fewer nurses being called in or sent home, would be well received, and indeed that aspect of the new system was not part of the nurses’ concerns. However, the nurses felt that the clinical and administrative parts of their job were suffering.

Specifically, they reported that at times they were unsure what a particular patient needed and had trouble identifying and finding the responsible physician, who could be anywhere in the hospital. Also, the overhead activities for taking care of many different types of patients took time—time that came out of direct patient care. Upon further investigation, it also appeared that the new system was not being followed as prescribed. That is, even after 6 months of data gathering, it was impossible to tell how much the new system could potentially save, because it was never fully implemented. That’s because the BMT was not immune to emphatic input from doctors and nurses. Hence, although the BMT tried to implement something close to the desired cycling, in the case of any one patient there could be passionate voices arguing for specific nursing units, so the BMT frequently departed from the prescribed recipe.

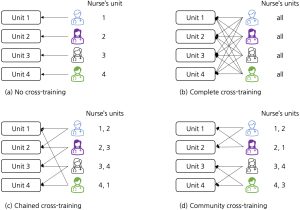

Bob went back to the drawing board using his knowledge of operations science and working with his internal team. Rather than focusing on artificially reducing demand variability, Bob focused on adjusting his nursing capacity buffer to absorb demand variability. In looking at flexible capacity options, Bob and his team determined that limited amount of cross training, option d in the illustration below, would provide the best combination of patient care, nurse satisfaction and cost.

Bob’s understanding of operations science and his work with his team led to a solution that worked best for the hospital, its patients and employees.

Encourage and inspire employees and sustain your operations success over the long term with a common language and operations management grounded in operations science. No software or consulting required. Contact us at the Operations Science Institute and get started on the road to long-term success.