Have you ever had to wait in line at a grocery store? Most people have. What is your strategy? Presuming most people want to spend the shortest time possible in line, you are looking for the shortest line. Is that a good strategy? Often it is not. This is a classic example of operations science in everyday life.

Let’s look at the grocery store checkout line through an operations science lens. The same concepts apply to any store’s checkout lines. What are the elements of demand and transformation? First, demand is pretty simple. It is number of people that show up at checkout with grocery carts, we’ll say per hour. Also to keep it simple, we’ll restrict demand to one person per cart.

Transformation is the act of changing an entity or set of entities or of changing the entities’ status. In this example, the entity is a cart of grocery items that is transformed from being store inventory to being a customer’s groceries, owned by the customer. Transformation, depending on the store, can vary. It is common to see three configurations of capacity in a modern stores.

1. Single cashier, single line, unrestricted cart content

2. Single cashier, single line, restricted cart content, e.g., 15 items or less

3. Many automated self-service stations, single line, unrestricted cart content

As it turns out, the longest line is often the shortest wait. This is because of queueing (waiting) which in turn depends heavily on resource utilization, in this case the resources are cashiers or self-service check out stations.

A simple application of operations science follows that shows how this works. The time to check out a cart of groceries depends of course on the number of items in the cart. Another assumption is made that people with full carts of groceries are not as likely to do self-serve check out because they don’t want the hassle. A simple model was created and average time to check out groceries (once you have reached the cash register) in each line is given in the following table

| Checkout Type | Number of Cashiers | Item Limit | Checkout Time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single cashier | 1 | No limit | 5 |

| Single cashier | 1 | <15 items | 2 |

| Self-service | 4 stations | No limit | 3.5 |

| Self-service | 6 stations | No limit | 3.5 |

Variability in time between arrivals to the cash register and variability in check out time (once at the cash register) also have an effect. In this example, the fewer-than-15 items line had the lowest variability. The variability for the self-service line was the highest and it was was four times higher than the fewer-than-15-items line. The single-server, unlimited items line variability was double fewer-than-15-items line variability.

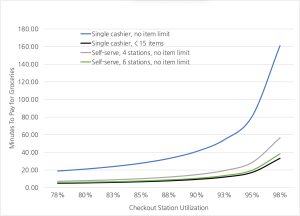

The results in the following chart provide a few conclusions about total time to pay for groceries, including wait time in line.

1. If checkout is very busy, go to the line served by multiple cash registers. This is usually self-service at grocery stores but it doesn’t have to be. If there is one line feeding multiple cashiers, that would make for a shorter overall wait also. At very high levels of utilization, for example shopping for groceries on Christmas Eve or the day before, the wait is much, much longer in the single-cashier-no-limit lines. You can pick any of those lines and have a long wait, it’s not that you picked the wrong line. You picked the wrong type of line.

2. There is a massive reduction in wait time when adding multiple cash register resources. Even though the checkout time (once reaching the cash register) for the self-service line is almost double the checkout time for the fewer-than-15-items line, the overall wait time is shorter for self-service.

3. When the cash registers are not very busy (less than 50% utilization), the difference in wait time is not nearly as pronounced.

This is a straight-forward everyday example of operations science in practice. On a more technical note, it shows how the buffers of capacity and time are related in a service operation (grocery store checkout). In operations science, there are often three buffers: inventory, time, and capacity. In service operations, there is no inventory buffer. In this case, an inventory buffer would mean that the customer walks up to the counter and the cashier gives them a receipt for their item from a stack containing receipts for every possible of cart of items that a customer could buy.

Encourage and inspire employees and sustain your operations success over the long term with a common language and operations management grounded in operations science. No software or consulting required. Contact us at the Operations Science Institute and get started on the road to long-term success.